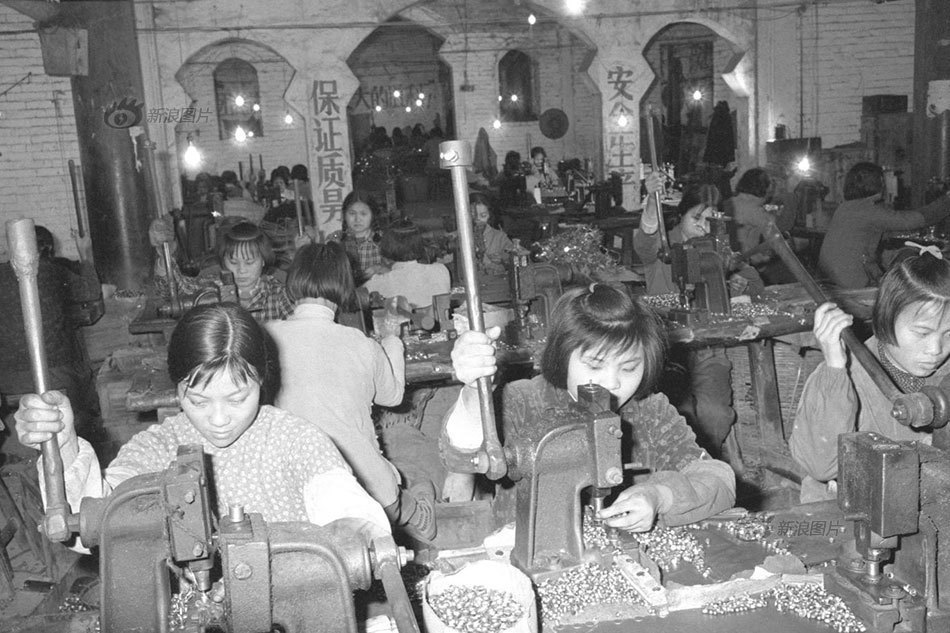

People involved in international trade in the ‘70s and ‘80s have told me that then the mere fact a Chinese factory was making a product guaranteed profit. It was tough for a buyer to find an authentic supplier and it was tough to set up a factory (due to limited investment and tight regulations). There were often several trading companies and middlemen between producer and buyer, pushing commodity market price higher.

The bygone landscape

Forty years ago, the system revolved around cheap labor and infrastructure capable of supporting it. Many factories couldn’t export directly, didn’t have English-speaking staff, and couldn’t connect physically or culturally with overseas buyers. So, either the manufacturer had the luck of connecting directly with an end buyer or go through middlemen (usually Taiwanese or Hong Kongese) who profited by bridging the cultural/language gap.

The early 2000s and its western middlemen

In the early 2000s changes happened. Factories took to the Internet and more English-speaking employees entered the workforce. The middleman’s profits and place in the supply chain dwindled as the factories started contacting customers directly. But the factories were more than happy to continue charging the same high prices customers were used to. It made owning a factory in the early part of this century a very profitable enterprise. This financial success combined with the loosening of free enterprise regulations made opening a factory much easier than in prior decades.

Simply put, the middlemen who didn’t start their own factories were out of luck, the factory bosses cashed in, and business continued as usual on the client side. The one exception could be seen in the few large, highly qualified factories that more significant clients wanted to work with. For plants that earned the luxury of being in high demand, those go-betweens were still required to serve as gatekeepers.

Huaqiangbei and the curbs of the electronics market’s shop

In 2006, Mr. Zhang ran a USB flash drive assembly line out of a small office in a Hua Qiang Bei market building. Hua Qiang Bei is downtown Shenzhen’s premiere electronics street where today rent prices are 10-20 times that of a factory. I bought from Mr. Zhang. Back then his prices were about the same as the larger factories and his assembly line was walking distance from my office rather than the hour’s drive it would take to get to the factory.

Four silent, skinny chain-smoking young Chinese men pumped out 2,500 USB drives per day–or more when overtime was required. The portly Mr. Zhang kept things running, fueled by tobacco and shots of strong tea, the preferred source of nutrition for many bosses from the Chaozhou region of Guangdong.

Salaries and rent were cheap back then; simply being in business meant turning a profit. It was a special time. I’m certain Mr. Zhang had a good run. I’m also certain his office is no longer open, because, today, an electronics factory (especially one that small) can’t sustain itself when tied to one product and run without the systems in place to make itself scalable. Because profit margins for new products are higher than for old products, if a factory wants to keep doing the same product, they must grow in size to compensate for the lower margins.

The advent of manufacturing processes efficiency

Because of the abundance of factories that have opened over the past 10 years, how well a factory is being run is more important than what it is manufacturing. While many Chinese electronics factories are selling finished products instead of manufacturing services, the big guys are not. Look at the largest factories in the tech space, the original design manufacturers (ODMs) like Foxconn, Quanta, Flextronics, Jabil, and Pegatron that are responsible for Tier 1 brand manufacturing.

Successful factories’ focus is on the process, not the product. They don’t make one product, they make many different products based on brand request. Their refined processes are mostly consistent regardless of the product being assembled. Today, when evaluating a mainland Chinese factory, look at the organization’s fundamentals: the integrity of the owner, the efficiency of production, factory conditions, and overall organization of human capital.

How the game has changed

Years ago, while I was learning what makes one factory better than another, I was also learning how products were made, the key parts of the supply chain, the origin of the parts, and that a factory’s production prowess carries more weight than their product portfolio. One doesn’t need to own or run a factory to learn about the supply chain; however, running a factory should expose the manager to lessons in how to improve manufacturing.

I met the guys making the cases for my MP3 players, the screens, the batteries, the IC chips, the USB cable–even the guy, and sometimes gal, making the screen’s little plastic cover. Components came from the same suppliers to ensure product uniformity, but we used multiple manufacturing locations to maintain a reliable lead time.

Owning a factory has never interested me. It’s not the right match for my talents. Fortunately, others embraced the challenge. Unearthing who does it best, I can compare cost and services, like consolidated purchasing, assembly speed, quality and after-sales support. Then–like any other commodity–I choose the best option (which is not necessarily the lowest price). Hatch’s expertise in managing commodity materials and services is part of its unique value.

Sometimes clients mistakenly believe that factories sell for the cheapest price. They have a hard time apprehending how Hatch, and similar companies, sell products at factory-competitive prices without our own assembly line.

The answer is simple.

The job of a factory isn’t to sell end products, but to make end products. And merely because a factory sells a product doesn’t mean they do so at the best price. Not all factories are run efficiently. Their inefficiencies require them to charge clients more. In many cases, inefficiencies lead to lower quality and delays, which also add to the cost in lost time and/or defective goods.

Hatch looks for assembly facilities experienced in whatever product it’s looking to manufacture as this creates efficiency and leverages proficiency. Hatch concentrates on integrating and pushing forward all the individual elements of the supply chain. The factory doesn’t need to have its own product development team. It’s sometimes better that they don’t so they can focus their attention on manufacturing. Hatch pay them competitive rates for on-demand assembly services while sidestepping extraneous overheads.

I envy the businessmen that made their fortunes in the ‘70s and ‘80s by getting their boots dirty and making connections with factories–but the market isn’t that simple anymore.

Forty years ago, a direct connection to a specific factory would almost ensure success. Now application of focused knowledge, adaptability, and experience keep us in the game. We work in conjunction with factories, helping make them better, but not being at their mercy as we’re the one making the product, they just assemble it. In the future, as robots start replacing human labor, manufacturing may leave China and the game will continue to change, bringing an interesting era and new opportunity. I wish this article helped you understand better electronics manufacturing current state for your project’s own good and that you enjoyed the reading! Ben @ HatchPS: If there is any topic you’d like us to cover just send Garry an email or a tweet to Hatch.