Discover key considerations when looking for a custom Android development partner. The quality of service matters as much as the quality of hardware.

Continue readingAvoiding & Resolving Custom Android Manufacturer Problems

Trying to find Mr (or Ms or Mx😋) ‘Right’ to handle development and production of your custom Android product? What are you looking for in your manufacturing partner? A smile? Cheap price? A yes-man? People with more experience buying from overseas suppliers would say no to all, but no one starts with experience (unless you’ve been reading a lot of this blog). Assume you find yourself in bed with the wrong partner. Things started out the way you want, but when it’s time for the supplier to deliver the nightmare begins. Something bad happens, you feel helpless and scared since you’re half the world away as Mx. ‘Right’ runs away with your heart, money, and time. China’s manufacturing industry has grown on the backs of hard working people, not a reliable legal system. Don’t expect it to help. Almost everyone buying from China faces problems with suppliers at some point.

There are endless ways of getting hurt by Chinese suppliers. Thinking about them is reminiscent of the question ‘how many ways can someone die’. This article highlights three of those situations that make decent case studies to learn from. The first covers a problem that Hatch had with a supplier. The other two examples come from companies that reached out to Hatch as a result of the problems they were having with their suppliers.

Fake Certification

Around 2012, when Hatch was producing high volume mass market Android tablets that ended up in large retailers, we had a supplier of power supplies (the device used to charge a tablet) that claimed to have UL certified chargers, which our client required. The price for UL certified charger is higher than the equivalent with no certification. An existing power supply supplier said they had UL certified chargers (at a higher cost). After checking scans of certification documentsthey provided, we made the purchase. In hindsight we should have called the company shown on the UL site to confirm the power suppliers came from them. Our customer was more vigilant about this than we were and pointed out, after the tablets had already arrived in the US, that the label of the power supplies we bundled with the tablets didn’t perfectly match the ones shown on the UL site. The cost to repurchase power supplies, ship them to the US, and repack 10k tablets exceeded $165,000 ($200k+ at present value). Money that came right out of Hatch’s bottom line.

When the problem was brought up with the supplier they made up excuses and then stopped communicating. To protect ourselves we had a signed written agreement with the supplier saying that if the chargers weren’t UL certified they would be responsible for all related costs. Multiple lawyers said that the contract wasn’t worth anything and we’d be wasting money hiring them.

A few lessons came from this. Firstly, we should have done more due diligence on the authenticity of the power supplies. Secondly, if we wanted any shot of legal protection then we should have let a Chinese lawyer handle that process from the beginning, rather than doing the contracts internally. Ultimately Hatch paid dearly for getting cheated (and Hatch’s owner had many sleepless nights).

Deception and Bad Quality

An early stage startup, pseudonym ‘Orange’, contacted Hatch about their custom Android project. The project was a good match, but their volume wasn’t enough to start working with Hatch. Orange found another supplier who agreed to the volume they wanted. Orange paid the supplier a deposit. When the time came to start production the supplier said they wouldn’t return any of the deposit until Orange shipped a higher quantity than they had agreed to. Coincidentally it was the same quantity that Hatch had required in the first place. The customer was stuck. Orange could either lose a year of development and their deposit or figure out how to get more money to start mass production. They found the money, started shipping products, and received the first batch with a 20% defect rate. Unable to rectify the situation with the supplier, who still had their full $50k deposit in hand, Orange was in desperate need of help. They reached out to Hatch again.

Although fixing situations like this falls outside of Hatch’s typical service offering, the owners of Orange were great people and we wanted to help them. Before accepting the task we reached out to the supplier, explaining that we’re the new China representative for the client and want to figure out the problem. We went in with an open mind, not with hostility or accusations. As long as the supplier was responsive and willing to cooperate we believed in the chance for success. Our investigation showed that the product had a few problems. The most glaring was that they were using low quality batteries. We worked with them to replace the batteries on the next production run (which was already produced, but not shipped), testing and approved samples, and convinced the supplier to replace the battery (at their expense) for 2500 pcs. At the same time we redeveloped the product for Orange, making improvements based on feedback from Orange, so they could work with Hatch moving forward. The redevelopment went quickly since we could use the existing product as a foundation.

In this case the supplier wasn’t a complete scam. It seems they just didn’t know what they wIn this case the supplier wasn’t a complete scam. It seems they just didn’t know what they were doing and instead of taking responsibility for that they put the onus on the customer to make up for their faults. Orange was in a tough position because their initial volume was 2k pcs and not too many companies would be interested in taking a custom Android project of that size. The owners of Orange are good people and took everything the supplier told them at face value, rather than digging deeper with their own due diligence (similar to the mistake Hatch made many years prior with the power supplies).

Supplier Goes Out of Business and Disappears

A company, pseudonym ‘Palm’, started developing a product with their supplier about 3-4 years ago. The product was successfully developed. Usually with custom Android development the client commits to a higher volume than they want to ship on the first production. The client pays a deposit on the full quantity, but only pays in full for the units as they ship out. This is a good idea for both the client and supplier when done properly. The first mass production exposes hidden issues or brings small optimizations to light that didn’t come up during trial production. It’s usually possible to implement improvements for the next mass production run. After starting mass production the supplier said they need full payment for the whole order quantity (meaning the ones that hadn’t yet shipped). Palm wanted to maintain a positive relationship and agreed to pay. The supplier then said that their business was having trouble and asked Palm for a loan. Palm wanted to help. They made the loan. The supplier disappeared.

When Palm recently reached out to Hatch they couldn’t resist explaining their situation, although their intention was just to find a new supplier. Hearing about their plight was enough to make Hatch want to help resolve the problems with their old supplier, even if that means it takes longer to ship out our first order with them. We’re following up with the old supplier, but unlike Orange, Palm’s supplier is clearly scamming Palm and doesn’t have any intention to rectify the situation.

Situations like this are tough to deal with, especially as China has been closed off since the pandemic started. Once a client starts transferring funds to an immoral or incapable supplier, and has no way to visit that supplier, it’s easy for a supplier to ignore them. Clearly this is not the way business should be done, but bad people don’t think about the right way to do things, they think about what they can get away with doing.

In retrospect the client should have done more to find help once the supplier asked for full payment in advance. That’s a major warning sign. Asking for more money on top of that made matters worse. Unless there’s a long term personal relationship in place that should never have been considered from a business perspective.

Avoiding Nightmares

Thorough and proper due diligence will reduce risk Ask for references. Not customary in normal Chinese business, but you’re not looking for the normal Chinese supplier. Make sure it’s a foreign customer. Don’t be afraid to ask questions. Hopefully the supplier has done such great work for them that they’re happy to help the supplier.

Have the supplier do tasks, like research different product architectures. Do they respond on time? Have they made any mistakes? Mistakes are fine, in fact they’re useful to have happened in the beginning, because they often happen during a development process. The concern isn’t about making mistakes, it’s whether the mistakes were identified and corrected or not handled the right way.

Does the supplier ask the right questions? Everyday of development brings countless questions. Asking insightful questions at the beginning gives you a chance to see that they care about a successful result, not just getting your order. More questions early also means less headaches at the end.

Resolving Hardware Problems After the Warranty Period

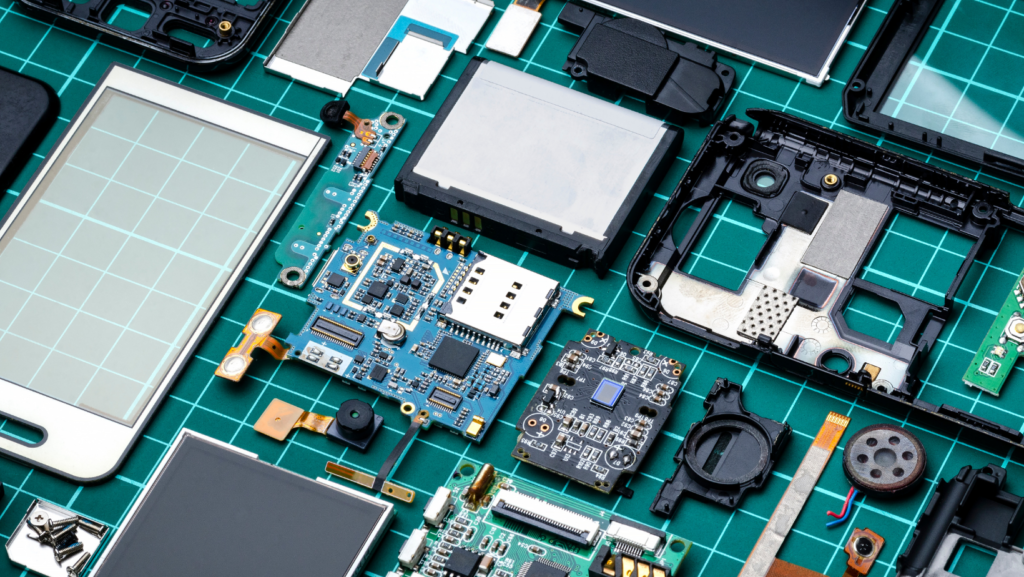

Most companies buying custom Android hardware or mass market (retail) Android products rely on their manufacturing partner for hardware knowledge or, at least, after sales hardware or components. The industry standard duration of manufacturer warranties is 12 months from shipping or date of arrival (be sure to clarify this with your supplier!). It’s common for brands to provide warranties that eclipse the time frame provided by their manufacturers. When their supplier’s one year warranty ends, how do these companies deal with servicing hardware problems? Even during the warranty period the question of dealing with defects is complicated.

In the case of a custom Android product used for business or commercial applications the brand is responsible for maintaining hardware in perpetuity. Hatch’s clients typically make money from a revenue generating service delivered by Android hardware rather than selling hardware for a profit. The brand needs to maintain the product for longer than that. With retail Android brands, end customers usually get a 12 month warranty from the date of purchase. There could easily be 5-6 months between shipping from China and when a customer buys the product.

Get spare units to cover expected defects with each order. 1-3% is typical. Send out new units to clients to replace the defects. Get back old ones from the clients, then swap parts as more come in (hopefully it’s not always the same part that breaks). Alternatively get spare unassembled components from the supplier, if that’s a better option. Usually it isn’t though. Keep a record of the key components from each production that can vary by production run like screen, touch panel, and camera. Sometimes suppliers use components from different manufacturers. Label products by production run so it’s clear which production the defects came from. When components change the drivers, and thus firmware, will be different. Sometimes components change to save money, other times it’s because the originals aren’t available anymore. If it’s impossible to determine which part to use when fixing, usually firmware can support multiple drivers. Supplier support is necessary to get that done. Then update the firmware to use the one with all the drivers.

When vetting suppliers look for those with a long term vision and integrity. This has massive value in that the products are usually better quality and the supplier has more to lose if they’re not better quality. Try to judge these intangible traits during initial communication and during the sampling process. Choosing a supplier isn’t only about cost as the commercial relationship has many angles. Cleaning up the mess of the wrong supplier will cost much more in ongoing fees than the lower upfront hardware cost saves. If the supplier stands behind their word, they’ll honor their responsibility or look for middle ground solutions with the client.

Dealing with product repair in-house increases turnaround speed and usually lowers cost compared with sending the product back to China for repair even if labor cost is high. Without getting into too much detail it’s usually difficult to import defective products to China. This is as much a country issue as a supplier issue. China makes it much easier to export than import products. Defects usually are blocked at customs or charged a very high tax. Combining the cost of not having the product, tax, and shipping usually makes shipping products back to China economically disadvantageous.

The keys to handling after sales service are finding the right supplier (not easy, usually takes costly trial and error), learning how to fix products locally, having the parts available to fix the products, and knowing which parts to use in each product.

Calm Before the Storm – Custom Android Tablet Manufacturing Before Chinese New Year

Have you tried shipping last minute orders before the Chinese New Year? Learn how to avoid missing orders due to supply delays around this holiday.

Continue readingAndroid Used as Leverage in International Trade Wars: How Did We Get Here? What Happens Next?

Android is being used as leverage in the trade war between economic superpowers, U.S. and China. Here’s how it escalated and what’s next for the industry.

Continue readingThe Nightmare we Share – Lessons from Working with the Wrong Chinese Android Supplier

Why avoid working with the wrong Chinese Android supplier? It’ll save you precious time and money. Learn from real experiences and avoid these mistakes.

Continue readingJuggling Curve Balls: Electronics Manufacturing in China – Part 2

This is a continuation of a previous article about what happens behind the scenes of production for large retail orders.

Continue readingJuggling Curve Balls – Electronics Manufacturing in China

Read about Hatch founder Ben Dolgin-Gardner’s personal experience with electronics manufacturing in China, and how companies there succeed in a tough industry.

Continue readingThe Do or Die of Shenzhen Manufacturing: A Niche to Scratch

Shenzhen was a sleepy fishing village that became the world’s leading electronics manufacturing hub. Learn how companies in this megacity compete, and what it will look like in the future.

Continue reading